Yverdon

1804-1825

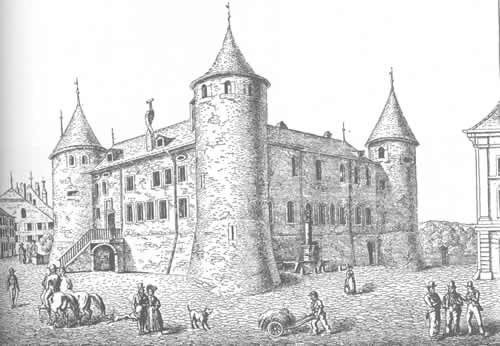

In the second half of the year of 1804, Pestalozzi started to set-up his new institute in the castle of Yverdon in conjunction with three fellow teachers. During this same time, Fellenberg was making very autocratic decisions at Münchenbuchsee and disliked anyone to contradict his views. As a consequence the mood of the teachers and pupils of Münchenbuchsee deteriorated to such a degree that many of the teachers and pupils transferred to Yverdon after six months.

Pestalozzi's institute in Yverdon became famous very quickly and his educational impulse extended first of all towards Germany and especially towards Prussia but also towards France, Spain, Italy, England, Russia and America. The institute was directed by a committee consisting of Pestalozzi and four of his colleagues. This committee chose a director for each class and took care of financial matters.

The institute was in its prime in the short period between 1807 and 1809. During this time the school community consisted of 165 pupils, 31 teachers and trainees, 32 "Seminaristen" and 10 members of the Pestalozzi family with their servants- altogether around 250 people. Pestalozzi's School for Daughters also belonged to the same community and was situated right next to the castle where there was separate education and classes for boys and girls.The institute always struggled financially because Pestalozzi accepted very low accommodation fees. Furthermore nearly one third of the pupils were not paying any school fees as many pupils were accepted free of charge whose parents were so poor they were unable to pay. The teachers did not receive wages, just their board and accommodation. The school was suffering from heavy economic losses due to a lack of budgeting and improper bookkeeping. The institute’s affiliated letterpress in particular suffered heavy losses.

During classes the pupils were taught in groups. Pupils who excelled in a subject were used immediately as teachers for their fellow classmates. Classes were long and the amount of lessons totalled about 60 hours a week. This is three times as much as what is common in schools in Switzerland or Germany today. Taught subjects were Maths (arithmetic and algebra), Morphology, Art, Geography, History, German and French, Religious Education, Science (Chemistry, Physics, Zoology, Botany), Latin, Gymnastics, Music, Bookkeeping and Letter Writing. As Pestalozzi's institute was meant to be an experimental school, the schedule was flexible and at certain times of the day the children had time for individual learning.

Pestalozzi approved of a tight co-operation with the pupils’ parents, inviting them to express their criticism openly and frankly. Every day visitors came to Yverdon and were able to observe every classroom activity. Pestalozzi himself showed the visitors around and took personal pride in the interest that was shown concerning the educational work of his institute. The teachers were obliged to inform the parents regularly about the behaviour and the progress of their children. Standard methods such as tests, marks and reports, which were introduced to schools at this time and common in most of the schools today, did not exist at Pestalozzi's institute. Pestalozzi did not want the children to be compared with each other and believed that the capacity of a child should only be measured by their own individual merits.

The qualifications of the pupils at the school were varied. Besides highly and normally gifted children, those who were maladjusted, mentally retarded or behaviourally disordered were also accepted to Pestalozzi's institute in Yverdon. The minimum age requirement for the pupils was 7 years old. No pupils over the age of 11 years were accepted. The children were educated until they reached the age of 15, unless they wanted to stay on at the so-called "Seminaristen".

The organised hiking trips with the pupils were an important part in the institute's daily life. There were no official ‘holidays’ as such but these walks often lasted a few weeks and the pupils were lead to the Alps and the surrounding countries. These tours were part of the Science and Geography lessons and were intended to be visual aids and vivid learning experiences for the pupils. In preparation beforehand, the journey and sight descriptions were read, maps were memorised and the equipment for the journey was organised. In addition lessons were often held outdoors to observe, describe and draw plants, shapes, animals or rocks. Pestalozzi also considered gardening and handwork a valuable part of education. The pupils were therefore taught to work with all sorts of tools such as saws, hammers. and planes. They learned to use a lathe, helped with the housework and worked in the institute's printing works and book-bindery. Sometimes they helped the carpenters, mechanics, watchmakers and tuners in town. They were allowed to own pets (mostly rabbits) and designed their own gardens. Sports and games were also part of daily life in Yverdon. The pupils regularly bathed in the nearby lake and all of them learned how to swim. In wintertime they built snow castles and when the lake was frozen over all of them learnt how to ice-skate.

Because of this way of life, everyone at the institute lived together like one large family. Most of the young trainee teachers (16 to 20 years old of the "Seminaristen") and head teachers lived liberally like their pupils. There were no strict rules and prohibitions, decisions were made after each incident on a case by case basis. Clothes were of practical usage only and were not seen as symbols of etiquette. The boys walked without shoes in summer and -contrary to the custom- they also did not wear hats. The staff was forbidden to humiliate, mistrust or lose their tempers with the pupils, physical punishment was not accepted. The teachers' only means of discipline was their personal authority, their aura and their persuasive powers, after-all they lived with the pupils, and even ate and slept in the same rooms.

Pestalozzi held the position of a leader and mentor and he liked to be called "Father Pestalozzi". He devoted himself mainly to his literary work, supervised the educational work of the teachers and insisted of being informed about the pupils’ weekly progress. He welcomed the growing number of visitors each day and reprimanded as was his duty when the situation arose. During feasts and holidays he held large speeches, from which a considerable amount of his written work evolved.

Pestalozzi's unique leadership style and unselfish behaviour towards others impressed all that visited Yverdon and was especially acknowledged by his contemporaries and close colleagues. However where there is light there is darkness and his personality was often paradoxical and inconsistent. He would often lose track of things and such disorder meant he was not able to manage his institute calmly. For 15 of the 20 years that Pestalozzi lived in Yverdon the mood was often poisoned by merciless arguments among the teachers. When the arguments became so serious that they could not be settled between the teachers themselves but in a public court, they started to damage the good reputation of the institute and finally ruined it altogether. One of the reasons for this situation was Pestalozzi’s obvious lack of organisation and executive direction. Karl Justus Blochmann, who was a teacher in Yverdon from 1809 till 1816, wrote about Pestalozzi:

"It was an unforgettable time when I used to work closely with him, he often seemed to have a childlike outlook but one tarnished with weakness. The purity and innocence, faith and love, gentleness and dedication of a child were a part of his soul until his death, but he had absolutely no calmness and stability, prudence and wariness, no control over actions or persons, none of those qualities that are part of a man […]. If the whole of mankind covered such ideals, Pestalozzi had not the slightest idea of how to lead a tiny little school in a village."

Consequently there was a unresolved argument at the institute about who made the better school head and who should become Pestalozzi's successor in future time. In particular, two of Pestalozzi's colleagues, Joseph Schmid (1785-1851) and Johannes Niederer (1779-1843) had an irreconcilable dispute about this issue.

Schmid, who was born in the Vorarlberg-Region in Austria as son of a farmer and who was later a pupil in Pestalozzi's institute, turned out to be a maths-genius and became a teacher in this subject very quickly. His extraordinary ability to train the pupils in maths started a rumour that the institute was set up only to educate mathematics. Pestalozzi had to underline several times, that not only the mental education but also the moral training was a central part of his education system. Schmid was an absolute loner with a strong will and dominant personality. Most of the other teachers did not like him very much because of his bad manners and his lack of consideration to his fellow colleagues. His merits were however that he had a strong sense of justice and a clear vision for realistic ideas. He always warned against arrogance and requested that the teachers be punctual and conscientious in carrying out their tasks.

Niederer, who was also a dominant type had already studied Theology and worked as a priest before he started as a teacher at Pestalozzi's institute in Burgdorf. He participated actively in contemporary philosophy and worked on combining Pestalozzi's educational doctrine with his own idealistic philosophy. He soon became the institute's main speaker, philosopher and publicity- manager. Holding this position, Niederer opened the institute's printing works and fought a hard literary war with Pestalozzi's opponents whereby he hardly had time for giving lessons. Niederer, like Schmid, also felt superior to his colleagues and intervened strongly in Pestalozzi's work.

In 1810 Schmid and Niederer had their first significant confrontation during a teachers meeting which resulted in Schmid and other teachers leaving the institute. Niederer however was not interested in practicalities and was absolutely incapable of managing the institute and its financial matters. He therefore re-approached Schmid to return who in the meantime had already reformed the education system in a part of Austria. As a further bid, Niederer even invited Schmid to be his witness during his wedding ceremony with the headmistress of Pestalozzi's School for Daughters in 1814. So Schmid returned to Yverdon in 1815 and immediately introduced a very drastic, but necessary reform: He ceased the literary war, closed the institute's printing works, introduced a strict bookkeeping regime, dismissed half of the teachers and increased the work load of the remaining staff. Because of these drastic measures, Schmid made a lot of enemies and a short time after the death of Pestalozzi's wife the arguments reached their climax.

Pestalozzi nearly despaired of the stubbornness of his colleagues; he beseeched them to reconcile and work together- without success. In 1816 sixteen teachers left the institute and at Whitsun 1817 the drama reached its turning point when Niederer, who was preaching in Sunday church suddenly stopped his sermon and angrily accused Pestalozzi of several preposterous things. After this incident they finally broke away from each other.

After Niederer left the institute a fight started between him and Pestalozzi. Niederer claimed Pestalozzi owed him money but Pestalozzi believed otherwise. He had already given him and his wife The Institute for Daughters. So Niederer took Pestalozzi to court and even when Pestalozzi gave him all that he thought was owed, Niederer still did not let up. Pestalozzi asked Niederer over and over again for peace but to no end. In a shattering letter written on February 1st 1823 (PSB 13, p. 16-18) he implores Niederer again for a reconciliation, but Niederer stays firm and does not want to accept any sort of agreement. According to this judgement however, Pestalozzi was in the right but nevertheless Niederer still did not give up. And so Niederer continued fighting until he achieved one of his aims: His opponent Schmid was forced to leave the Kanton Waadt and later the Kanton Aargau, where the Neuhof is situated. So Schmid moved to Paris where he tried to realise Pestalozzi's educational ideas in his own institute.

Despite all these issues Pestalozzi's literary work written during his Yverdon period was very extensive. In this edition only parts from "Ansichten und Erfahrungen" and "An die Unschuld" are considered. Furthermore other works from the Yverdon period are worth mentioning such as the third version of "Lienhard und Gertrud", "Geist und Herz in der Methode" (1805) and "Über die Idee der Elementarbildung" (Lenzburger speech). But above all the most important of all his numerous speeches is Pestalozzi's birthday speech held in 1818.

In "Geist und Herz in der Methode" (PSW 18, p. 1-52) Pestalozzi is of the opinion, that people should not judge his institute based merely on the success of a class. Judgements should be made on things that can be measured directly such as cheerfulness, devotion, faith in the teacher, obedience and willpower. He emphasises that education should not be purely based on what one learns externally but the be stimulation of our inner abilities and power. He also stresses, that the power of the brain and the power of the heart do not have the same value. Intellectual education cannot provide the power that gives the human being the realisation of ones internal nature and of the divine inner spirit. According to Pestalozzi these feelings are not developed by the power of the intellect but by the power of the heart and love. In Pestalozzi's opinion the advantage of this ‘method’ (which he later labelled as an ‘idea of elementary education’) was the connection between thinking and love: "it teaches the child to love in all thinking and to think in all loving." (PSW 18, p.37).

Pestalozzi worked in Yverdon on several writings at the same time as these speeches, many of which were later revised by Pestalozzi himself, copied and edited by colleagues and were prepared to go to print. In Pestalozzi's lifetime just excerpts of his work were printed from "Ansichten, Erfahrungen und Mittel zur Beförderung einer der Menschennatur angemessenen Erziehungsweise" (in short: "Ansichten und Erfahrungen").The available text is based on 20 handwritings and in the published edition there is also work of Emanuel Dejung, the long-term editor of the "Kritische Gesamtausgabe" . Pestalozzi starts this text by looking back on his life and explaining the development of his educational career. Once again he describes his basic ideas of a natural education with the main emphasis on a moral-religious education which is based on a domestic education. According to this theory he develops a set of standards that should be applied to every educational lesson and describes certain criteria in order to evaluate it. For Pestalozzi it is important to prove, that his method can and must be adapted to different social situations. Furthermore he discusses the question of how the educational system in his country can be reformed and how teachers and politicians can influence such decisions - ??and of which importance an experimental school with its personalities (teachers and influential politicians) would be.

In 1809 the "Gesellschaft der schweizer Erziehungsfreunde" (Swiss Society of Friends of Education) was founded and Pestalozzi became its first president. During the foundation ceremony on August 30th 1809 Pestalozzi held a big speech, the so -called ‘Lenzburger speech’ "Über die Idee der Elementarbildung" (PSW 22, p.1-324). His colleague Johannes Niederer revised the speech, added a lot of his own ideas and sent his version to the printing works. So Pestalozzi's passionate and metaphoric script was interrupted by a rather arrogant and philosophical script style, which shows Niederer’s efforts to integrate Pestalozzi's methods into the ideas of Schelling.

Since the breakdown of his home for the poor in Neuhof in 1780 Pestalozzi never abandoned his hope to rebuild it. He therefore never considered selling the estate to aid his financial crisis. But these hopes were disappointed in the year 1807, because he did not get the support of the government he had wished for. However ten years later his dreams were realised: In 1817 the publishing house Cotta and Pestalozzi made a contract to publish Pestalozzi's works. Pestalozzi wanted to spend the earned money exclusively for educational projects. In a speech held on his 72nd birthday Pestalozzi announced the re-opening of the Neuhof institute against poverty and promised to spend the expected 50.000 swiss francs to sponsor his educational efforts, the education of teachers, the construction of sample schools and the permanent revision of the book "Mutter- oder Wohnstubenbuch". But as always, things turned out differently as planned. His colleague Schmid undermined the Neuhof revival. So as an alternative, a house for the poor was founded- but in Clindy and not in Neuhof which was connected with an industrial school and an institute for teacher education. Only one year later the new institute merged with the main institute in Yverdon but broke down with it in 1825. An additional complication was that in 1821 Pestalozzi did not receive the expected 50.000 swiss francs but only 10.000. Finally in 1824 Pestalozzi was forced to address his failure and retracted his donation. (PSW 27, p.111)

Pestalozzi's speech at his 72nd birthday on January 12th 1818 (PSW 25, p. 261-364) is one of his most expressive works. The first print consists of 173 pages and is particularly interesting because it is written without the participation of Niederer. Pestalozzi expresses himself in this work with his former passion, genuine script style and philosophical freedom. He illustrates the link between social and mental educational by using biological images. For example Pestalozzi uses a plant to show the connection between humans and education. He describes the growth and development of a tree as a metaphor for the development and maturing of the human being:

"The image of education or the inner holy creature of a better education is shown in the metaphor of a tree, which is planted beside the creek before my eyes. Look, at what it is. Where does it come from? Where do its roots, its trunk, its branches and twigs, its fruits come from? Its seed was planted into the earth and so the tree’s spirit was planted. There is the nature of the tree. It is the seed of the tree” (PSW 25, p. 265)

Pestalozzi always compares the human being with the tree: the spirit of the tree is concentrated in the seed and transformed by the spreading of root, stalk, leaf, blossom and fruit without loosing or changing its inner nature. He adapts this theory on the inner spirit of the human being, which in the beginning is physically constrained by its animal instincts but later develops a complete human existence whose life is navigated by love and faith. A marshy, over-fertilized or dry soil can hinder the development of a tree and a good soil can promote growth, but it cannot create the tree's nature. Similarly the spirit of the human being is not created by its surroundings but only supported or hindered by them in the development of its nature. But Pestalozzi is realistic enough to see the limits of his metaphor: The human organism is an animal but not an animal, 'it is an organism with a biological disguise which hosts a living a divine creature (PSW 25, p. 268). Contrary to the tree, which cannot escape from wind and weather, good soil or bad soil, the human being is free. It can decide to what extend it wants to use outside influences. A few years earlier Pestalozzi used the picture of a growing tree to describe the mutual influence of education and our own influence of our own abilities. He wrote one of his few- maybe his only- important poem:

Jung geschützt, Jung gezogen, Jung geschützt, Jung gedrükt, | Young protected, Young pulled straight, Young protected, Young oppressed, |

In the later course of his speech Pestalozzi talks about one of his keenest concepts: To improve family education with a book, which shows the parents -especially the mother- the correct way to bring up their children. If enough people know about his methods on education for classes, the elementary lessons could take place at home. By 1803 the book "Buch der Mütter oder Anleitung für Mütter ihre Kinder zu bemerken und reden zu lehren" (PSW 15, p.341- 424) was already published, large parts of which were edited by Pestalozzi's colleague Hermann Krüsli.

According to Pestalozzi’s principle that experience is the basis for knowledge and therefore all knowledge should be based on the experienced man, he describes exercises in his book. These aim to examine the connection between our own abilities and our bodies. However, Pestalozzi was aware that his book was just a first attempt and that it would need a lot of further work in future. The speech shows that in 1818 Pestalozzi still dreamed of a book that was an instruction for all fathers and mothers to educate their children in the correct way. It was so important to him that he even spent a part of his donation to work permanently on this project. The Link34 "Briefe an Greaves über die Entwicklung des kindlichen Geisteslebens" written in 1818 and 1819 can be seen as a preliminary work for such a book. Today they only exist in English translation, the original letters disappeared.